This article describes some code we developed to fix an issue with our Memcached environment. This took the form of adding a method to a class that we didn't own. The article then describes the way that we used the Watchdog gem to ensure that our class extension won't cause problems further down the road.

The problem

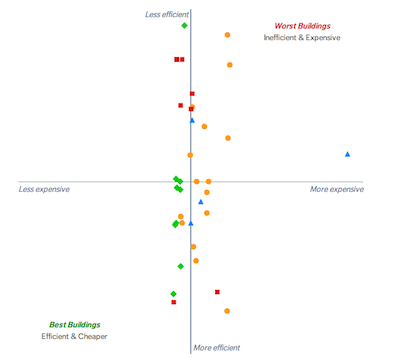

We use Memcached both for page fragment caching and for caching large collections of objects that require significant work to generate and fetch. For example, we have a page where we need to display a dot on a scatter plot for every building owned by the user. Associated with each dot is a small amount of work to 1) get associated data out of the database and 2) perform calculations on the data to get derived values that are used in the display of the scatter plot. This work is negligible for small numbers of buildings, but for users with thousands of buildings the work adds up to unacceptably long request times (actually they hit our self-imposed server timeouts first). For these larger accounts we simply can't afford to perform all those database queries and calculations during the server request cycle.

Instead we cache all that work server-side so that a request for the same data can be served up directly without the need to fetch most data from the database or perform any calculations. We also employ an aggressive cache-warming strategy so that data is usually pre-cached when a user requests it.

There's much more to say about how to implement effective caching in an enterprise Rails application. Here we just want to talk about a specific pitfall we ran into with our caching setup.

For our caching we use the built-in caching mechanism in Rails along with the

dalli gem, which provides a Memcached caching store called

ActiveSupport::CacheDalliStore. This allows us to cache objects using the

following simple API:

The way this works is that if the key "the_meaning_of_the_universe" is found in

Memcached (called a cache hit) then we can skip the expensive calculation

contained in the block. If the key isn't set (called a cache miss) then we

do the work but then send the value to Memcached so that we can avoid the work

the next time around. We can also do Rails.cache.read, which will read the

value but do nothing if there is a cache miss, and Rails.cache.write, which

will write the value without checking first to see if it already exists.

Every time you check the value of a cache, or write to it, you are making a request to a Memcached server (and a cache miss followed by a write will actually be two requests). Unless your Memcached server is running on the same machine as your application server there is going to be some network overhead associated with performing a lookup. The more keys you check for the more that network IO will add to the time of your request, which will eventually defeat the purpose of having a cache in the first place.

To avoid this it can make sense to perform a Rails.cache.read_multi operation,

where you pass a list of keys and get back a hash of keys and values, with the

value set to nil where there was a cache miss. This was the strategy we took

on our page with the thousands of buildings displayed on a scatter plot. The

code looked (very roughly) something like this:

That is, you perform a bulk read on the keys and then go back and fill in the ones that were missing, instead of checking each one.

In general this strategy has worked out well for us. The problem (finally) that

we ran into is that with our particular hosted Memcached provider and very

large accounts we would get strange behavior. Sometimes the page would load

right away and other times it would take minutes to generate, with no rhyme or

reason. When we looked into things it turned out that sometimes the

#read_multi operation was failing and we were treating the result as an empty

hash. This meant that the page had to go recalculate and write the values for

all of those buildings, even though the values actually existed in Memcached.

The solution

For whatever reason our hosted Memcached provider couldn't handle the large bulk read request we were sending them. The obvious solution was to break up the request into smaller chunks. To this end we created the following logic:

A quick explanation of the code:

- take in a list of cache keys

- get the chunk size from a parameter or from an environment variable

- chunk the keys

- perform

read_multioperations for each chunk - combine the results into a single hash

In practice this new method has the same method signature (when the chunk size

parameter is omitted) and output as the original read_multi method.

Next problem

The only problem remaining was deciding where to put this method. We try to keep

methods out of the global scope, so we wanted to put it on some logical module

or class. We discussed briefly the possibility of overriding

ActiveSupport::DalliStore#read_multi and using alias trickery to call the

original read_multi inside the new implementation, but decided against it on

moral grounds. We decided, however, that it would make sense to put the method

on ActiveSupport::DalliStore as an additional method, so that any code that

was previously using Rails.cache.read_multi could just switch over to using

Rails.cache.read_multi_chunked. In other words we could do this:

(Note that we can drop the reference to Rails.cache and just use read_multi

now, since an instance of DalliStore is what Rails.cache referred to

previously).

We liked this because it allowed us to look for our read_multi_chunked

operation in a familiar place, but we were also aware that we had opened us up

to a somewhat unlikely but nevertheless troubling risk that is inherent in all

such extensions: what if the maintainers of Dalli decided that they needed a

method that could handle chunked read_multi operations and what if they

implemented a method with the same name? We wouldn't necessarily notice the

change when we updated the gem. There might be subtle differences or

implications of their implementation that could affect our application. What if

the maintainers updated internal code to use their new method, which would now be

using our own implementation instead?

That might sound like a lot of ifs and in this case it's hard to think of a way that there would be a catastrophic effect (since it's unlikely that "read_multi_chunked" could mean something radically different), but it highlights the general issue with creating extensions on classes that you don't own. If nothing else, you might want to know about and use the maintainer's version of the method because it could be more efficient and you can stop maintaining your own version.

The extended solution

WegoWise maintains and uses a gem called Watchdog (written by a former Wegonaut, Gabriel Horner) that you can use to put an end to all this fretting about hypotheticals involving collisions with upstream code. By now it's a pretty old dog (last updated in 2011) but that's because what it does is fairly simple. Watchdog will check to make sure that your modification to a class doesn't collide with any existing methods. It performs this check at runtime so the moment upstream code creates a method that you are extending you will get an exception.

To use Watchdog you need to convert your extension into a mixin module. This is

necessary because Watchdog needs to hook into the extend_object callback

method that is run when extend is called on a class. This is what our code

looks like with Watchdog:

The new version is certainly more verbose, but we think that's acceptable.

If it wasn't clear by now, we are okay with occasionally modifying classes that we don't own. Sometimes monkeypatching (or freedom patching!) can be the most elegant solution to a problem, especially when you want to make a change to an interface that is called in many places throughout your codebase.

That said, we don't think that class modification should be your first, or even second, option when thinking about a software problem. There are usually better approaches, such as creating a wrapper class that you can define your own methods on, or creating a subclass of the class that you want to modify. If, after careful consideration, you still decide that you want to modify that class, we think it's reasonable for there to be some ceremony and cruft involved.

Watchdog makes extending an upstream class considerably less dangerous, for those occasions when a patch seems like an appropriate option.